The Death of Ontology

Once upon a time, all good software used some sort of a command language. Whether it was a word processor like Emacs, a typesetting program like TeX, or even something like a graphing program, everything had a command line at the bottom and some kind of command language that could be used to control it. Learning to use a piece of software meant reading the manual to see what commands it had, and what kinds of modifiers and arguments those commands took. There was, I expect, a whole science behind the creation of good command languages. I know, for instance, that many allowed you to use abbreviations so as they were unambiguous, so the better designed ones used a vocabulary that was carefully selected to be memorable but with no words that shared more than a couple of leading letters.

Then with a single innovation, the entire science of command language design became forever irrelevant. Command languages disappeared completely except in a few odd cases; even those depended more on its use as a scripting or programming language rather than a way for a normal user to manipulate the program.

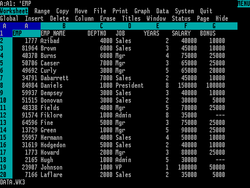

[caption id="attachment_240" align="alignleft" width="250"

caption="Lotus 123 with Menus"] [/caption]

[/caption]

That innovation was the invention of the menu, which I first remember encountering in Lotus 123 during the early 1980s. No longer did the user have to keep the manual handy or memorize a large vocabulary of commands, trying to remember whether this particular piece of software used 'open' or 'load'; used 'close' or 'quit', instead she simply selected the command from a list of available options displayed on the screen. No longer was there a complex structure of command arguments and command modifiers, instead many commands launched a dialog box where the user could specify options or select a target.

The old approach had a few advantages -- for instance, it was more amenable to scripting -- but the ease of use of menus won out and it was only a few years before every program had menus. Those who had studied the somewhat arcane skill of designing good command languages soon found themselves working side-by-side with the buggy-whip repairmen.

I see a similar transformation occurring right now. When my wife was studying "Information Science" (librarians, for instance, may take this), she spent a whole unit studying "Ontology". Ontology, as I understand it, is the creation of a taxonomy and/or specific vocabulary for describing a field of knowledge. For instance, "Cooking" is a field of knowledge, and if you were compiling an index for a cookbook or a cooking site, you might want to decide whether to group recipes into "soups, salads, entrees, deserts" or "breakfast, lunch, dinner", or any of hundreds of other ways they could be organized.

But the innovation that will obsolete the field of ontology has already appeared. The first of these was good, quick search engines. The fundamental trick for rapid searching is the hash table, but when that is scaled up to the size of Google's index, it takes on a whole different meaning. I often don't bother to look in a manual or help pages because (astonishingly) it is actually easier and quicker to type few words into Google and search the entire internet than it is to activate a program's help features.

It used to be that an ontologist could argue that searching still required one to know what key words to search by. But a couple of days ago I heard a friend describe how she learned to move archived emails from one program to another. Searching for "eudora email export" didn't turn up any useful results, but when she simply typed "eudora email", then waited to see what the "Google suggest" feature displayed. Right there was "eudora email transfer", and now that she knew what keyword to use, finding the information was easy.

The massive scale of the data available on the Internet or to a company like Google makes it unnecessary to have an expert produce a carefully designed vocabulary for a topic. Instead, we can effectively mine the collective mind of all of humanity (or at least that tiny portion of it that gets typed into searchable form on a network somewhere). Those words that are frequently used to define the topic become the correct vocabulary for describing it. Like menus, this requires a two-way flow of information between the user and the system, but my friend's example shows that this two-way flow already exists. And a professionally designed ontology is likely to be more effective in many ways (just as a command language could be more powerful and scriptable than menus), but I think that is unlikely to stop people from abandoning well-organized bodies of knowledge in favor of those that handy to search.

Posted Mon 29 December 2008 by mcherm in Programming